The Irish Potato Famine is such a well known disaster with such an obvious way to avoid similar problems in the future, that you would think mono-cropping with a single species of crop was a thing of the far past. It was a tragic disaster, caused by the combination of oppressed people being forced to subsist on tiny tracts of land, growing the one variety of one crop they knew they could survive on almost entirely, but without variety in species or the built up knowledge that comes from many generations farming a crop. Social issues aside, the way to avoid similar problems in the future would be to plant a wide variety of species and keep careful records. An easy fix.

The Irish Potato Famine is such a well known disaster with such an obvious way to avoid similar problems in the future, that you would think mono-cropping with a single species of crop was a thing of the far past. It was a tragic disaster, caused by the combination of oppressed people being forced to subsist on tiny tracts of land, growing the one variety of one crop they knew they could survive on almost entirely, but without variety in species or the built up knowledge that comes from many generations farming a crop. Social issues aside, the way to avoid similar problems in the future would be to plant a wide variety of species and keep careful records. An easy fix.

Never Out of Season: How Having the Food We Want When We Want It Threatens Our Food Supply and Our Future by Robb Dunn explores the world of mono-crops, exposes how in the case of many crops we are closer to a famine-level tragedy than you think, and the importance of research in preventing future disasters. Dunn focuses on a few specific crops, such as bananas, cacao trees, cassava, and potatoes, and how we came to grow just a few varieties of each in many places around the world (often not where the plant is native). With each crop he also explained the diseases they are susceptible to and how those diseases are spread. With the amount of current world travel, the threat of diseases travelling and wiping out huge amounts of a crop is constant and high (that’s why you get asked if you were in agricultural areas when you travel internationally).

Dunn’s true passion is the consistent research that must take place all over the world to ensure we are constantly breeding plants that are resistant to ever evolving pests and diseases. Saving seeds takes a lot of time and space, as you have to constantly grow crops and resave the seeds to ensure they are viable (the longer you keep a seed, the less likely it is to germinate). It also takes a massive amount of effort to find different varieties of a crop so you have a genetic bank of different traits. With genetic modification we can do some trait modification quickly, but for the most part this is a slow game. Plus, it is just about impossible to predict how diseases and pests will evolve and therefore how a plant will have to defend itself in the future. Preserving as many varieties as we know of makes for the largest safety net.

Dunn’s main call to action is to advocate for constant and large-scale research, as well as participate in the study of plants, pests, and diseases by keeping track of what you grow and see, and participating in diagnostic communities like https://plantvillage.org/ and citizen science projects. He does mention buying sustainably grown, heirloom crops at the end briefly, but I think that call to action can be much stronger.

As cooks we can easily gravitate to the familiar. We like recipes that we can rely on and replicate with consistent results. With the wide availability of ingredients, people thousands of miles apart, in different climates, can cook the exact same recipe. In all likelihood if you are buying something from a supermarket, you are getting the same varieties of zucchini or asparagus that they are also selling around the world. Farmers are not encouraged or emboldened to try new things, because the usual is what sells and farming is a volatile enough profession as it is. But we can be more supportive of their experiments. We can buy produce that we are unfamiliar with and cook it, both because it may be delicious, and we will be preserving and passing along the knowledge of that plant. Maybe the next time powdery mildew or blight or an undiscovered (or yet to exist) disease strikes, that heirloom or hybrid will have a previously unrealized resistance.

Farmers markets are about to get into full swing, so it is the perfect time to visit, get to know your farmers, ask questions, and buy some funky produce. The ones I know are friendly, passionate, and proud of what they grow. They want to answer questions and grow things you are interested in eating. Which is the whole point of this endeavor! Find interesting and delicious things, and eat them. We can just do it in a way that promotes biodiversity at the same time.

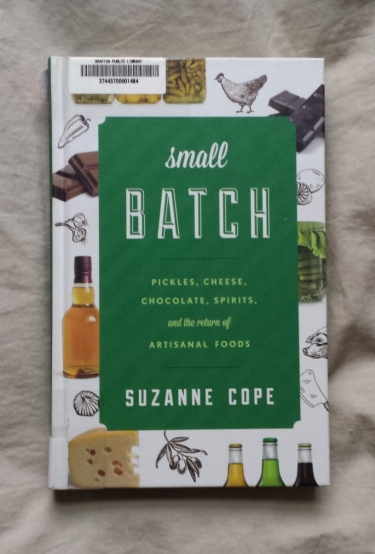

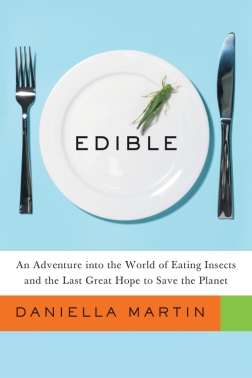

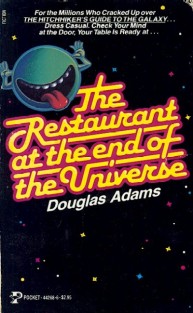

My favorite hobbies are in order: eating food, making food, reading about food. While the first two take precedence to sustain me, I wouldn’t be fulfilled without the third. The holidays are an especially great time to share this love of reading. While I don’t force food books onto everyone in my life, if I had to pick a few to share, these would be at the top of the list.

My favorite hobbies are in order: eating food, making food, reading about food. While the first two take precedence to sustain me, I wouldn’t be fulfilled without the third. The holidays are an especially great time to share this love of reading. While I don’t force food books onto everyone in my life, if I had to pick a few to share, these would be at the top of the list.